Background Material for Chapter 3

The Struggle for American Values

from Family Stories …and How I Found Mine

by J. Michael Cleverley

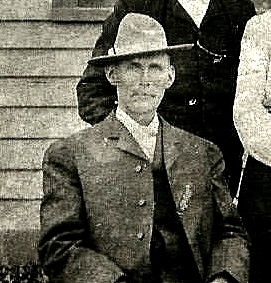

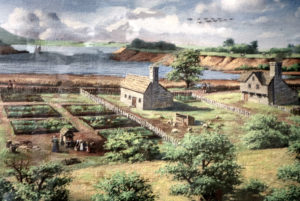

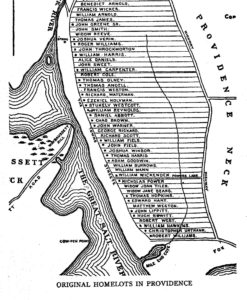

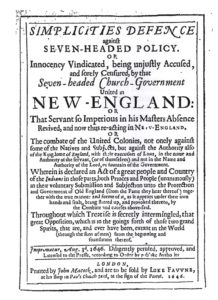

My grandfather’s grandfather Charlie Leonardson and his bride Ida May Dawley came to Idaho with their small son Arthur in 1883. Their homestead became the Leonardson Ranch where my grandfather, Wayne, grew up and my mother was born. Reaching back 10 generations, Ida May’s ancestors were settlers, too, in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Not long after they arrived from England, some moved and many were exiled to the Rhode Island colony where they struggled to promote the values Americans today take for granted: religious and political freedom, the right to live without state oppression, and democratic governance. It was never easy. The Puritans surrounding their colony often made their lives miserable.

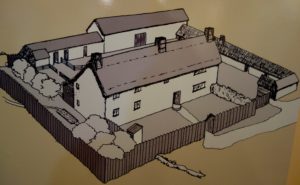

The troops, wounded and dead, who fought in the Swamp Battle were carried through the snow to the Blockhouse for care and burying. The Narragansetts never forgave the colonials for the atrocity, and in their response ravaged Rhode Island, burning every building, including the Blockhouse, south of Providence, except one. Today, flowers grow above the mass graves, and a lonely plaque reminds us of America’s most costly war (in per capita terms).

The troops, wounded and dead, who fought in the Swamp Battle were carried through the snow to the Blockhouse for care and burying. The Narragansetts never forgave the colonials for the atrocity, and in their response ravaged Rhode Island, burning every building, including the Blockhouse, south of Providence, except one. Today, flowers grow above the mass graves, and a lonely plaque reminds us of America’s most costly war (in per capita terms).