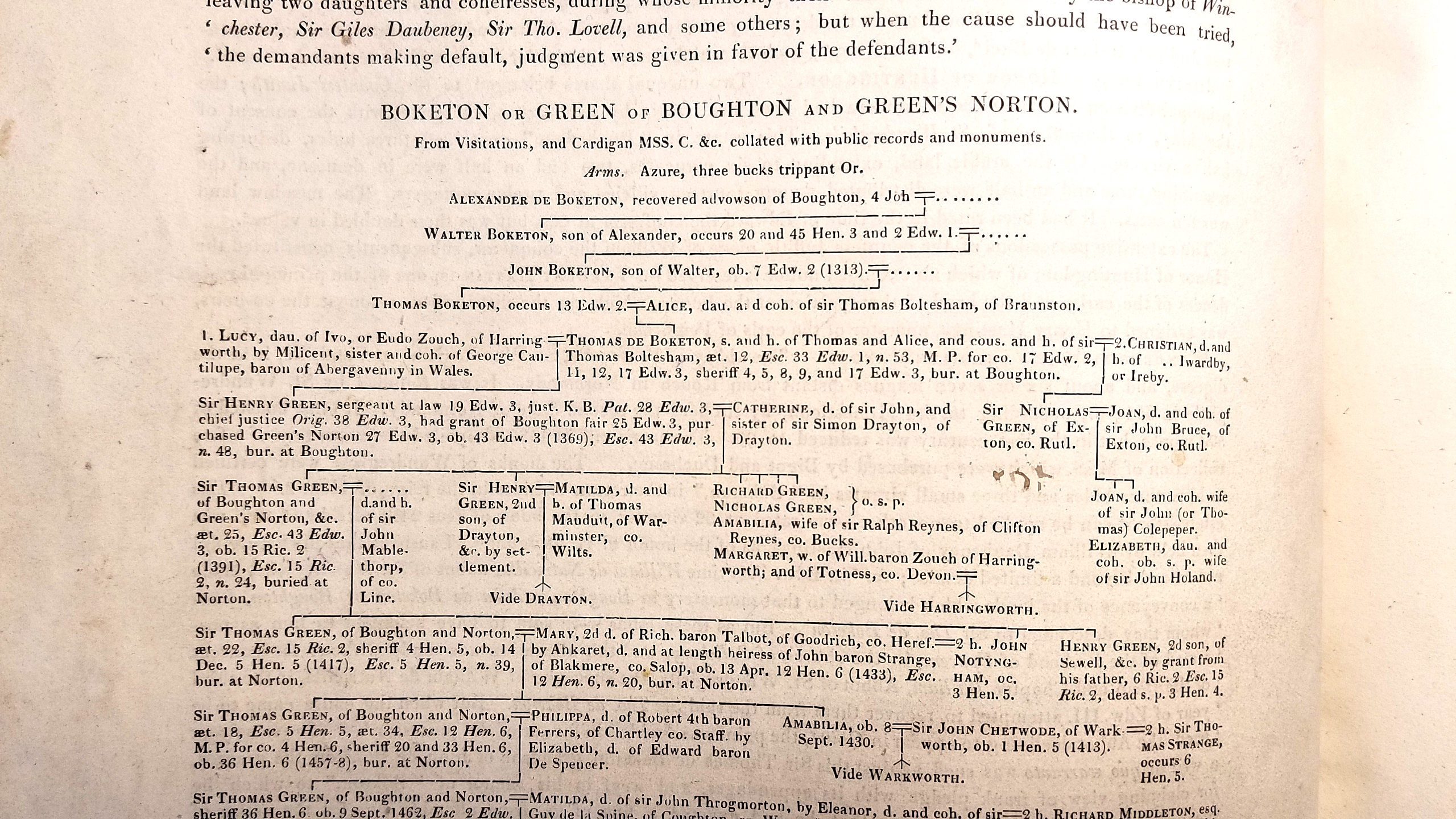

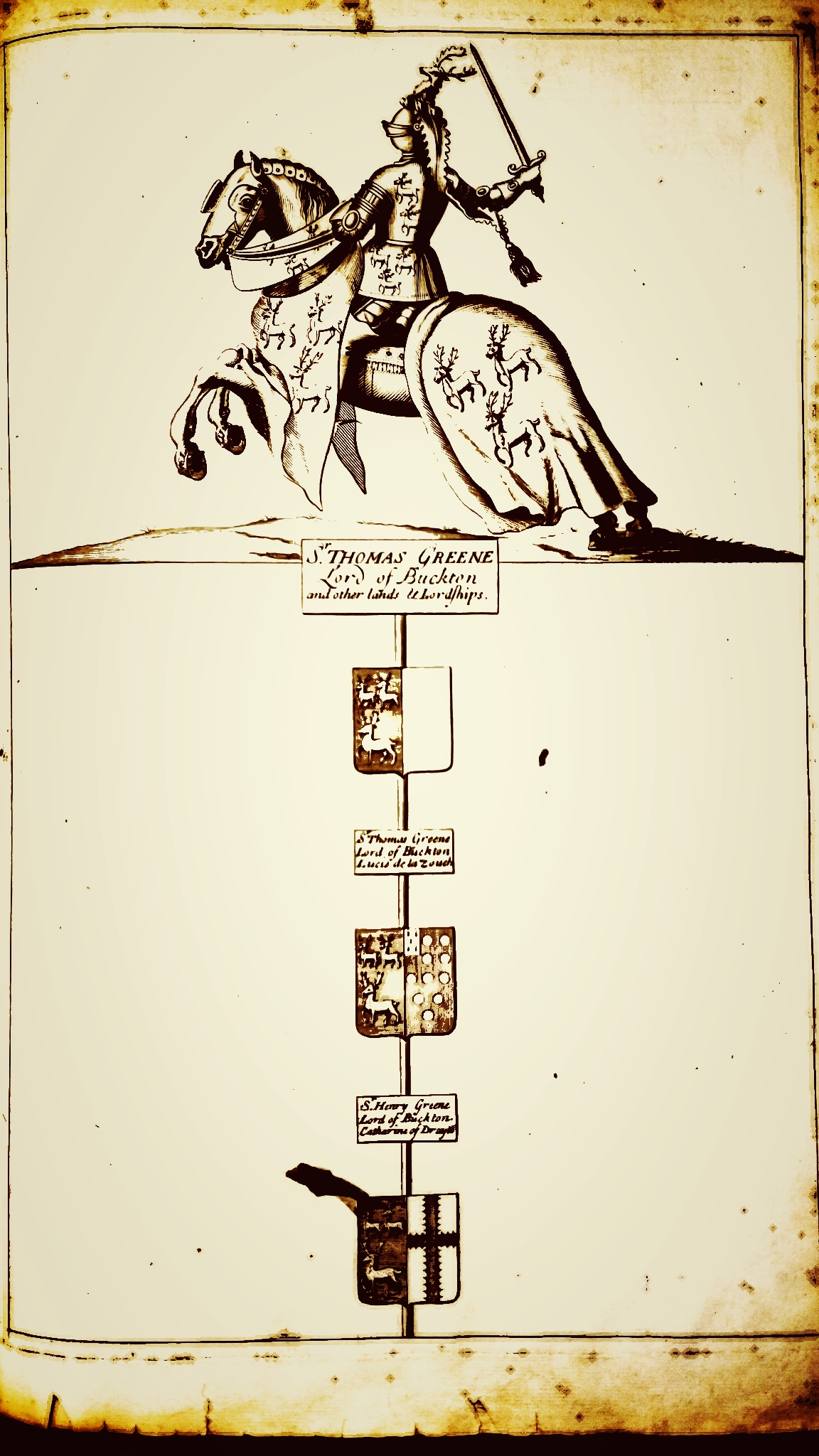

Before starting on one of our trips to England, I researched locations where some of the stories occurred. However, I was not optimistic that places where people like Sir Henry Greene and Lady Catherine Drayton lived nearly 700 years ago still existed. I was wrong. One evening while googling I discovered Drayton House near Northampton. The historic old estate was more a palace than a house. Sir Henry and Lady Catherine Greene lived there in the 14th century. Their son, Henry, and his wife, Maud, lived there, as well.

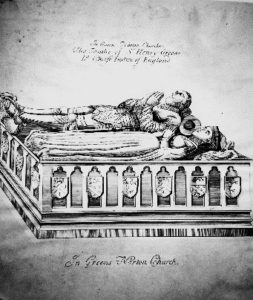

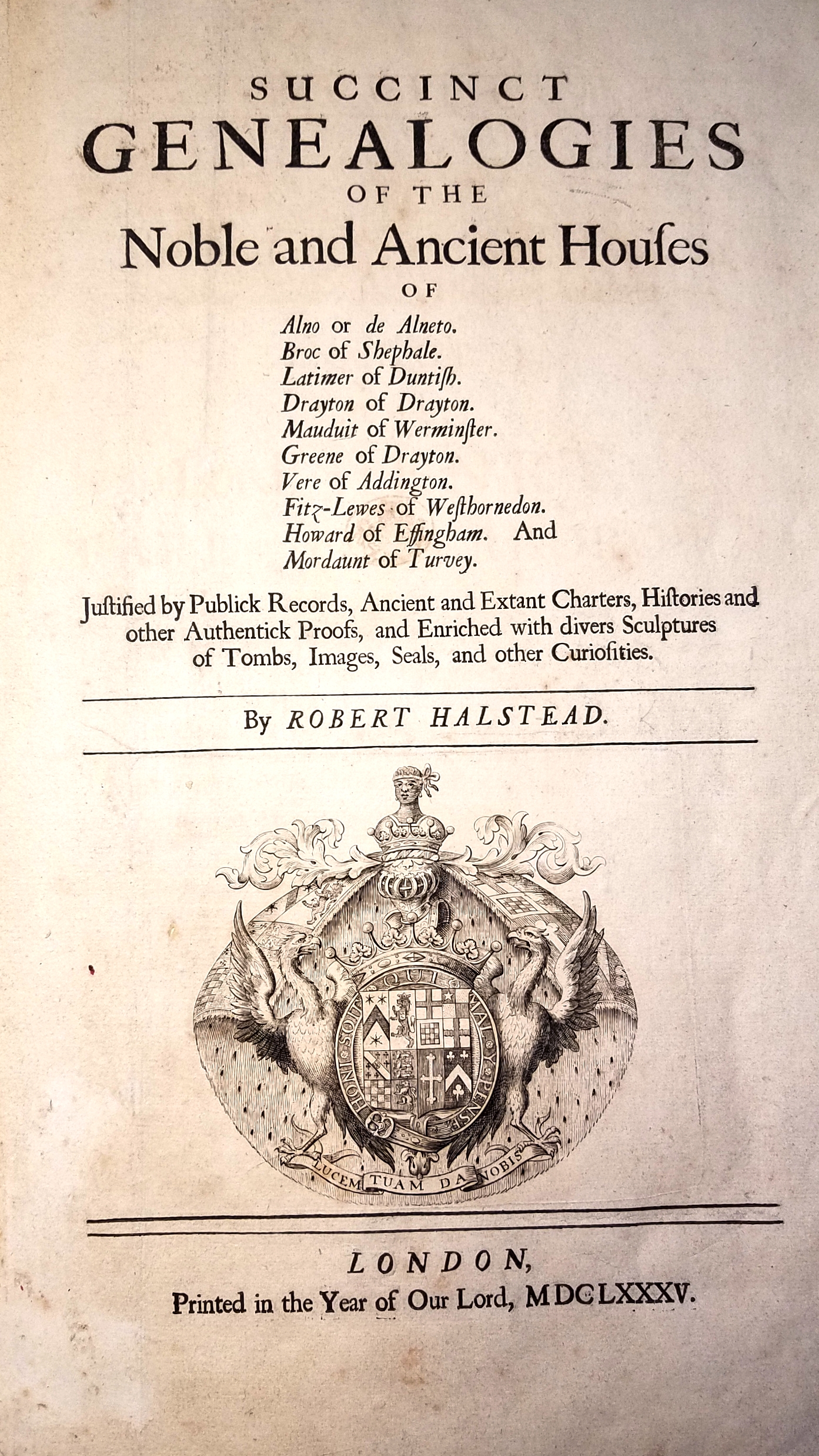

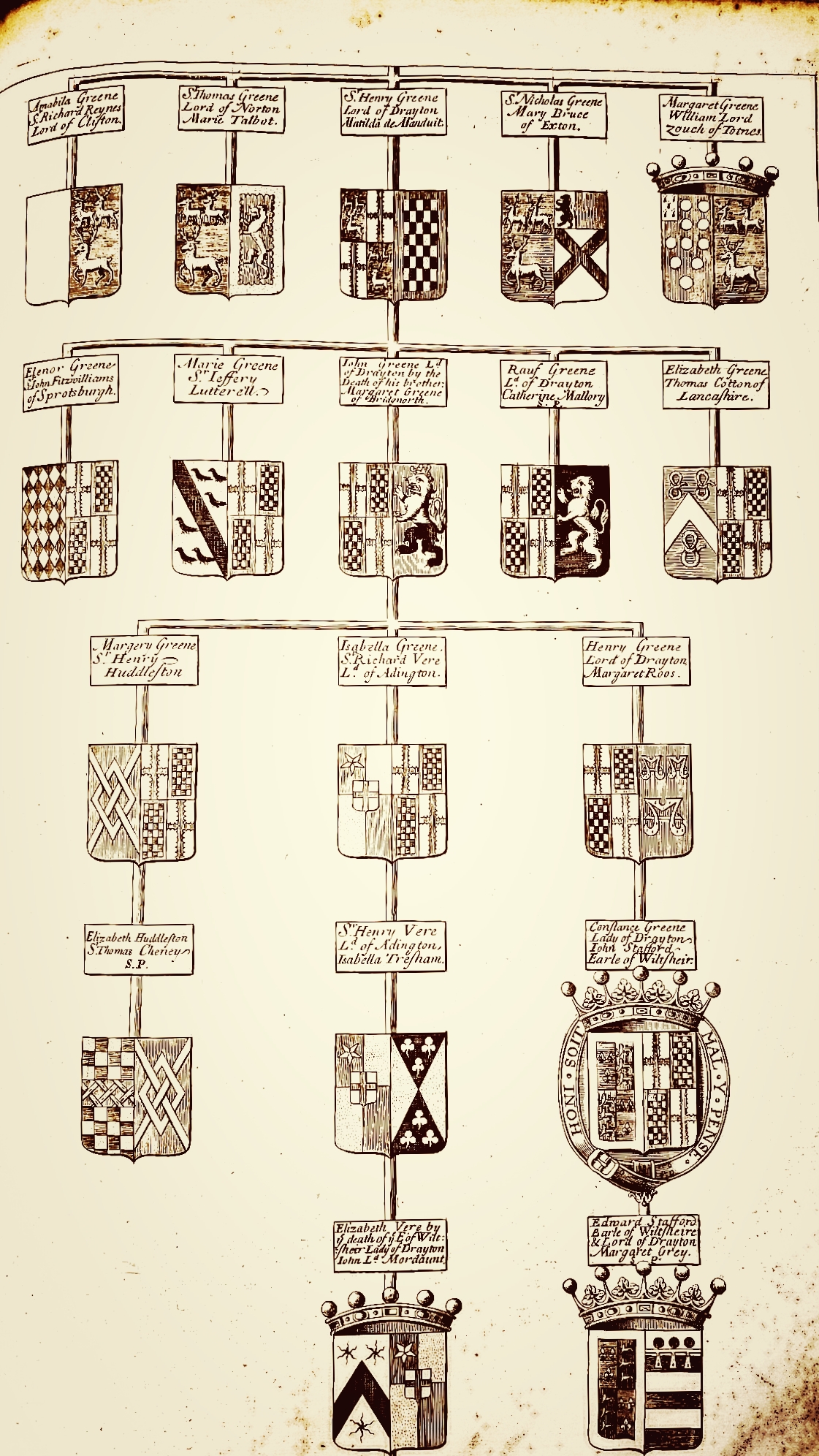

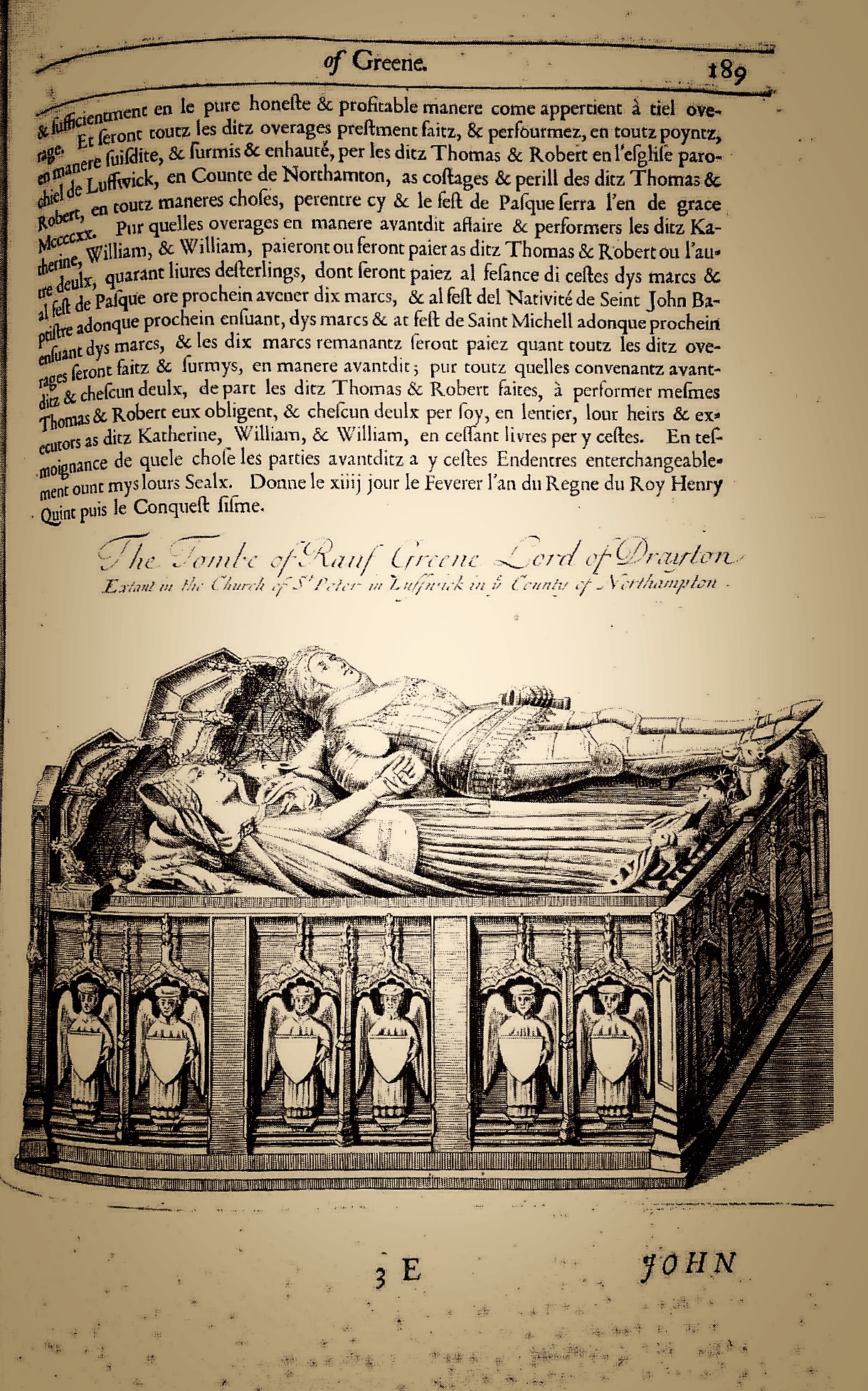

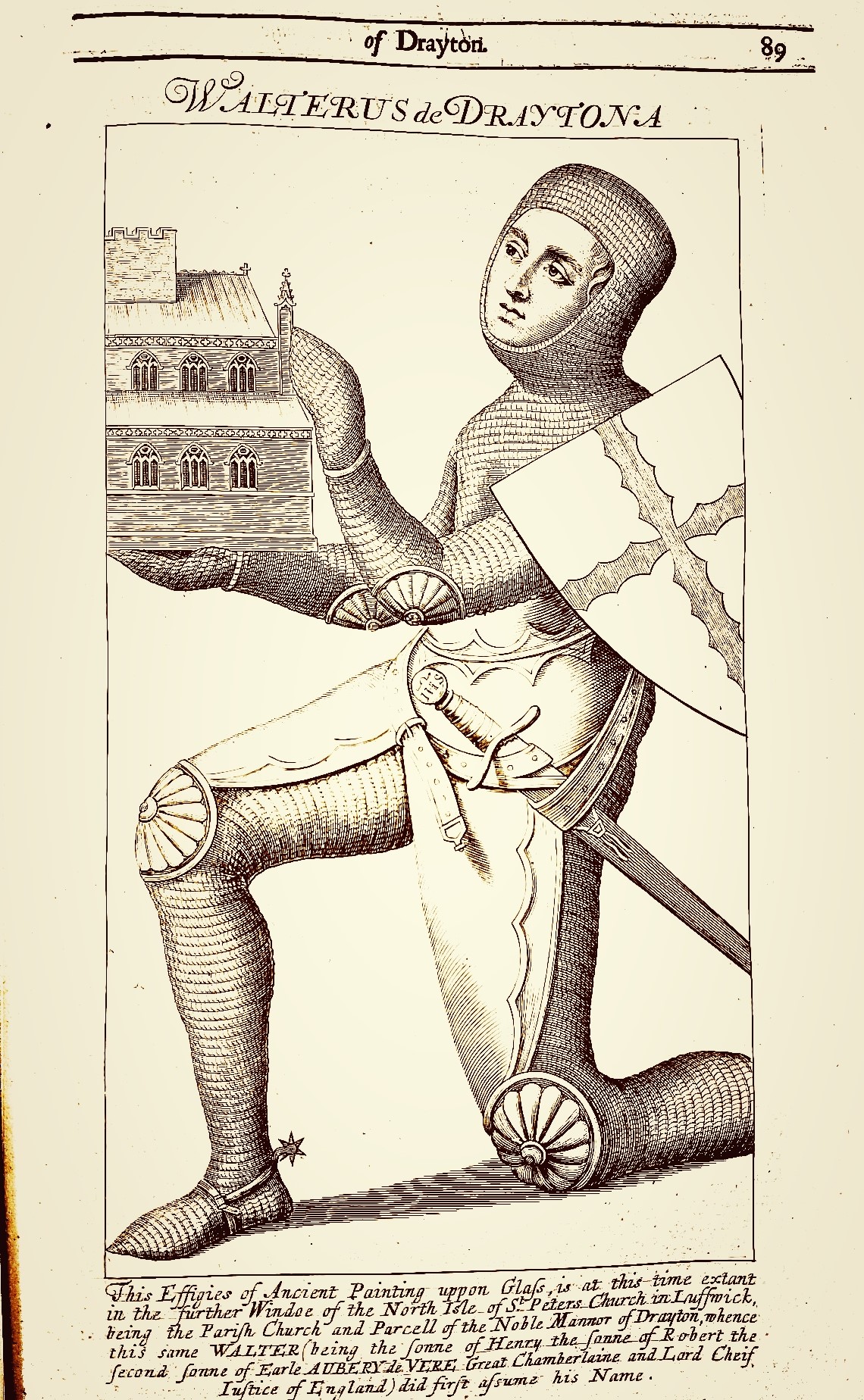

In about 1300, Catherine’s brother, Sir Simon de Drayton, built the first portions of this beautiful home. I later found in Halstead’s Genealogies a copy of the original document where John transferred Drayton House to his cousin, Henry Jr., upon the death of Sir Henry, Sr. Now, seven centuries later, the old house spread out from its original hall to include several Baroque and Neo-Classical wings built much later. This was just one of many that Henry and Catherine might have considered home, but it was Catherine’s family estate, and it was not far from where Henry was born. Today, Drayton House was situated elegantly as the private residence of the Stopford Sackville family whose ancestors had lived in it continually since 1770.[i]

Timing was perfect, and I hoped there might be an opportunity to visit Drayton House during our upcoming trip to Britain. A few months later, my wife Seija, our friend Mary Lou, and I were rambling in a rental car along the narrow roads, with charismatic houses, green fields, and pastures on either side, until we finally turned onto the 5,000-acre Drayton House estate. There were pheasants in the fields and sheep and cattle grazing near the gardens. It was a working property and a living home, far from just another old historical country estate.

Drayton House’s curator welcomed our visit. As we walked through its medieval halls and corridors, he explained how the property had developed and grown over the centuries. The Great Hall harkened back to times when the Greenes dined there. Even though it was now adorned in a later epoch’s style, it was still easy to imagine the days when distinguished guests from the shire, or from London’s center of power, visited and shared an evening with the lords and ladies who hosted them. On the walls hung large portraits of monarchs, many of whom had visited. The outside stone walls were built high enough to protect against invaders during medieval society’s disturbances.

The Stopford Sackvilles, we learned, descend from their ancestor Lord George Germaine who was the first of their family to own Drayton House. What a surprise. Lord Germaine was a familiar name to American colonists who, like our family members, fought in the American Revolution. As Secretary of State for North America under George III, Germaine managed Britain’s handling of the American revolt. From London, he formulated British policy toward the Colonies and very much micromanaged the British campaign, many say to its detriment.[ii]

Here was another great historical round. Germaine, who prosecuted the war against America, and Sir Henry Greene, whose descendant Nathanial Greene was one of the most effective American generals against Germaine’s armies, both owned and lived in Drayton House. George Germaine and Nathanael Greene had this in common: without Germaine’s bungling and Greene’s generalship, there might not have been the American victory at Yorktown. It occurred to me that fine old homes such as Drayton House have their own stories and souls that reflect the people who once lived in them.

[i] Bruce Bailey, Drayton House, (Drayton House, Northamptonshire, 1990). Halstead, 96-97.

[ii] Germaine’s unsuccessful micromanagement of the war in the Colonies was widely criticized in London during and after the war. See John Ferling, Almost a Miracle, The American Victory in the War of Independence, (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 2007), 265-267, 566.