Background Material for Chapter 10

Two Rivers Join

from Family Stories …and How I Found Mine

by J. Michael Cleverley

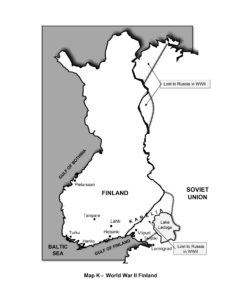

When my wife Seija Kaarina and I wed, we adopted each other and the past that had made us who we were. It was figuratively like two vast rivers from different pasts that arrived at a confluence. Their waters ran together to make a still broader channel that flowed into the new lands of the future. This was the river that carried the memories, stories, and traditions our children would inherit. They were heirs to the many families of the past, who lived along the river’s tributaries.

I was captivated by her family’s rich background, even though their stories were rarely easy. Her parents and grandparents knew war, loss, suffering, and grief. But they also knew redemption, reconciliation, and re-birth.

“Where Two Rivers Join” (Chapter 10) of my book is her story.