Background Material for Chapter 8

What was Your Name in the States?

from Family Stories …and How I Found Mine

by J. Michael Cleverley

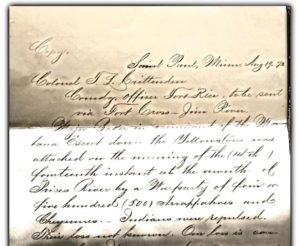

How do you track an ancestor who doesn’t want to be found? Actually, not a few of those migrating to the Old West came for that reason, to disappear. That was Richard McGuire. He was my great-great-grandfather, not so far back. When I was young, I even knew his and Mary Ann’s daughter, Mary Emma. Yet several generations have tried to track their stories. And it has been a lot of work. For one reason, someone trying to remain undetectable often changes their name. And that is what Richard McGuire (or was it Joseph Wilson? or, Richard Wilson?) did. Only a very few knew his real name, and when they did, they didn’t tell. He told freely the day he was born, but we still are not 100% sure what year.

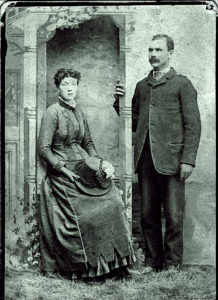

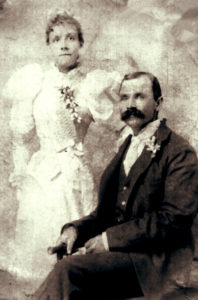

Mary Ann Taylor and Joseph Richard McGuire Wilson

Mary Ann Taylor and Joseph Richard McGuire Wilson

g picture of the couple. They left immediately for Arizona. Mary Ann made entries in her Bible for their two sons who were born and died on the same days in Arizona.

g picture of the couple. They left immediately for Arizona. Mary Ann made entries in her Bible for their two sons who were born and died on the same days in Arizona.

When they slowly lowered Richard’s coffin into the ground, the answers to scores of questions about the quiet unassuming man were buried with him. With no little irony, however, Richard’s mysteries born from secreting his stories kept him alive in the memories of many of his children and grandchildren. As far as I could tell, however, his mourners on that day in 1902 would probably have never heard or guessed about all this.

When they slowly lowered Richard’s coffin into the ground, the answers to scores of questions about the quiet unassuming man were buried with him. With no little irony, however, Richard’s mysteries born from secreting his stories kept him alive in the memories of many of his children and grandchildren. As far as I could tell, however, his mourners on that day in 1902 would probably have never heard or guessed about all this.